I know how this article ends because I’ve written it before. I wrote it two days ago and promptly lost it between the cushions of the Internet, and I’m now starting it again.

Losing my original writing and having to start over again has actually helped me to write an even better article, more clearly expressing what I was trying to get at the first time. That is, that writers should probably have a good idea of where they are going before they begin.

A friend of mine was recently reading Under the Dome by Stephen King. He said he was enjoying it so far and that it was exciting and a page-turner, but that he was worried about the ending. He was hoping it was all going to be worth it. I did my best to encourage him to keep reading without letting him know that, indeed, the ending sucked.

I don’t need to know!

In Under the Dome, a small New England town is mysteriously enclosed in a giant invisible dome. This gives King the chance to do what he does best: bounce a bunch of characters off each other—most of whom are a-holes—and see what happens. And in that sense, the book is a huge success. But the moment the first character asks, “What’s up with this invisible dome that just showed up out of nowhere?” I get very worried. When something huge and unexplainable happens in a TV show or book, the explanation is almost always “military experiments,” “aliens,” or some variation on “the Christmas spirit.”

And, if you know that one of these explanations is coming, when it finally does arrive it is so disappointing it makes you want to throw the book across the room.

But, like I said, I think the book on the whole is a success. The only huge disappointment is the explanation of the big unexplainable mystery posed at the beginning. This is something that has dogged a lot of long-form fiction. Many TV shows and novels draw a reader in with unexplainable mysteries so tantalizing that even though any explanation seems impossible, the reader or viewer just has to keep on watching or reading to see what could possibly be going on.

The two biggest recent examples I can think of are Lost and Battlestar Galactica. Both series drew audiences in with premises that were largely steeped in mysteries. What is the island? What is the smoke monster? Why do the Cylons want to kill the humans? What’s with the ghost Starbuck?

In the case of Battlestar Galactica, the finale was largely satisfying. But when it came to some questions that had kept people watching, the answers ended up being a resounding, “Uhhhhh….”

Another unanswered question: Why are Starbuck and Boomer both girls?

The ending of Lost was a mixture of that same “Uhhhh” mixed with “Dammit!” The “Uhhhh” from the mysteries the show just plain ignored, and the “Dammit” from the answers the show gave that either didn’t satisfy, or worse, were way too similar to theories that fans had in season one that the writers had flatly refuted.

Don’t bother asking.

Of course, its possible that no answers would be satisfying enough to match the tantalizing power of the mysteries themselves, but that’s a subject for another article (check your local listings!). The point is that when writers pose an intriguing mystery, they are setting themselves up for fan hatred down the road unless they’ve got it all worked out beforehand. Yes, they’ll buy themselves a lot of buzz and excitement as fans trade theories, but in the end, as in the case of Lost and to a lesser extent Battlestar Galactica, the fans will end up knowing that they’ve simply been toyed with for years.

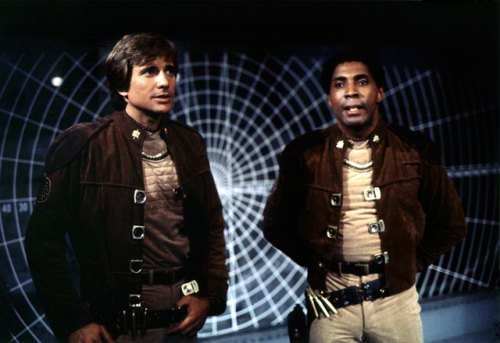

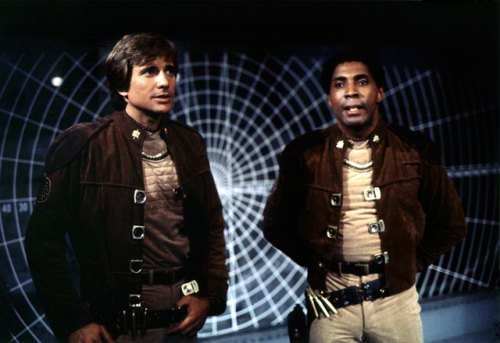

It occurs to me that the only long running TV show that I can think of that had a number of huge mysteries at its core, and which eventually provided interesting and satisfying answers, was the often dorky but ultimately great science fiction show Babylon 5. Sometimes the reveals of these answers were clunky, other times they were properly, well, revelatory. But most importantly, by the end of the series, viewers had the sense that this five-year show was one cohesive story, and that it had been moving to that ending all along. And in fact, creator J. Michael Straczynski says that the entire arc of the story came to him in a flash all at once before he even started writing the show. Whether or not that is totally true, it feels true as you watch the show.

Dorky? Oh, yes. But satisfying!

I would argue that Lost, on the other hand, was a big case of the emperor’s new clothes and that the audience mistook teasing mysteries and non-linear storytelling for excitement and brilliance. It’s easy to make something seem cool when it’s unfinished. Because it could be anything, but you can’t imagine what. “There’s a bunker with food and a record collection underneath the island? What’s going ON??” Battlestar Galactica was more successful, though it was clear that when it came time to answering some of it’s most intriguing questions, the ones the audience most wanted explained, the frank answer from the writers was, “We honestly have no idea.” And Stephen King gave himself an excellent setting for his story, but it was a setting that required the kind of explanation he just could not provide.

I can’t beat up on him or any of these writers, because I’m currently in the same boat with a book I’m writing. I’ve got a neat situation that all these characters are running around in, but it’s a situation that demands an answer to the question, “How did this happen?” Or even “What is going on?” Do I flip a coin between “the military” or “aliens”? Or do I leave it frustratingly vague? Or do I promise to answer the questions in the next book?

Whichever I choose, I think I’d better figure out what I’m doing now, rather than try to retrofit some sense to things at the end. Otherwise I’ll be guilty, like a lot of writers, of stringing my readers along with a lot of what look like intriguing mysteries but are really just empty promises.